WINTER IN PLASTER

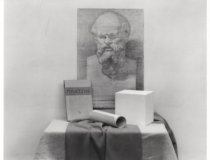

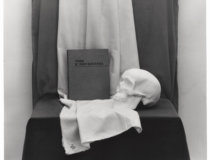

In this letter (or at least at the beginning) I am trying to address my younger self who is staring longingly towards a window in a drawing classroom in Soviet Vilnius, circa 1986, across the heads of other teenagers in front of a plaster one, whoever it might be: Plato, Socrates, Voltaire.

The latter, I remember, bears all those valleys of light and darkness on his face, crowded together in a gleeful smile, a subject of higher mastery of half-tones used to create the illusion of volume — the reason why all of us (including himself) are in this classroom. And some hair too, a different materiality to pay respect to, even if it is all cast in winter, no, plaster, forgive me: words slip and spill, and may remain so. Something similar to Plato’s or Homer’s beard, perhaps in a different winter though.

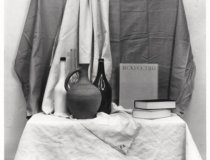

My younger self is immersed in reproducing this face covered by kids’ dirty fingerprints. He hasn’t read any of these authors. Maybe a few lines of Voltaire, maybe a few lines of Plato, maybe just a fingerprint. The pencil strokes are sparse, the shading does not bring out anything, and the so-called ’soapy’ quality is building up. “Put some more effort into the contrast between the drapery and the plaster,” the teacher advises knowingly — probably for the hundred and fiftieth time this year, always to a different set of ears, and without ever invoking the contents of whatever these gentlemen in plaster might have written. But we are in an art school, not a philosophy class. And summer will come soon; we will be able to go to the streets to draw from nature, en plein air: a true delight because then we will wander almost endlessly – as long as the weight of the etiudnik allows – in search of a motiv, without any commitment to reproduce anything.

Back indoors winter turns out to be long: the sun does not cross the window even once. But who knows — maybe the window is on the wrong side, maybe the class doesn’t start until late — no reason to verify the facts. Facts are like stars in the sky: one can always make new constellations out of them. Probably this letter to my younger self has been written many times before too, and in different places, but I don’t remember if I’ve ever finished it.

This time I start with some trepidation:

“I think I know how you feel: you feel stuck. But I am not sure I can help you out. Trust me — I know that feeling very well: the sense of being trapped in a sentence or in an irresolvable state. Or in obsessive hesitation. That sense of being consumed. To be honest, even a pleasant state of being can bring about that feeling of enclosure — a sense of being unable to terminate one activity in favour of another. And then there are worse things: think of being in a supermarket and feeling a growing sense of panic, the terror of spending too much time there, comparing products and prices. But you’ve only been to the local univermag so far — God bless that serene time spent over minimalist counters… (Hey, will someone please stop me from reproducing this received wisdom?!)

“Obviously my letter may not reach you — I happen to rarely send things directly. And you’ve also proved to be good at misunderstanding things. The perfect match with strings attached, albeit misplaced.

“I am convinced you are taking these plaster heads more seriously than you should. But at the same time you are dreaming of a future where you do something ‘out of imagination’, as you call it, ‘out of your own head’. That’s why you are looking at the window. And this is where I am writing to you from — from far beyond your imagination. You may be surprised: this place is in Moscow — a city that you associate, first of all, with Sviridov’s ‘Vremya’ tune. The ‘Dobroe utro’ tune too. To make matters even more complicated: I just bought a set of 12 watercolours today. Neva. You probably haven’t had time to forget them yet, even if your fingers are smeared with oil paint, bought by Slavka, your father’s friend, in the special shop for members of The Artists’ Union in Vilnius. What a shrine the place is: so many beautiful things that only the initiated have access to! Slavka is obviously a member — you are dreaming of becoming one too. Do you feel somehow reassured of the continuity of time and your artistic pursuits when I tell you that I bought a set of Neva watercolours? Or do you feel it’s a step back in your career? ‘Cause you are already dabbling in oils… Well, at least it’s not a set of Soviet gouache. But allow me to admit, I would love to travel with the scent of it in my bag. And allow me to skip some chapters forward: you’ve become a journalist, just like your father.

“It’s a good reason to leave that drawing you are stuck with unfinished. No harm to the future; it’s not the first thing you’ve started and left half-way. You’ve probably noticed that yourself.

“(I promise that’s the last existential remark I make in this letter.)

“But I have to admit that I am standing in front of something akin to a plaster too: a rather indescribable one, with no eyes and hair, but at the same time with all possible elements of the world in it; here I stand, hesitating between reproducing what I know and what feels like a total void, or total abundance.

“Do you think I can reproduce that constellation of a void and abundance with the 12 Neva colours?

“(Now I really promise I’ll stop with existentialism. Maybe even with my letter today.)

“This morning in Moscow I visited the studio of Alexandra Paperno, an artist, whose exhibition I had seen a few months ago. When I saw her work I was touched by the way she dedramatises her subjects, be it history, stars or classrooms. Her exhibition was wittingly calm, especially on the subject of ruins: they appeared as a relaxed paradigm of life, a quiet order of things. On my part, I feel I have a tendency to overdramatise situations, both in everyday life and in fiction. For the sake of some emotional effect perhaps, be it sheer ridiculousness or wonder. The way Alexandra spoke about art and life glowed with a certain tender tonality that had the power to soften up emotional relations one might have with the Soviet system or even with the stars in the sky. ‘Jarkyje, no tusklyje,’ she described the colours. I felt so familiar with those Soviet still lifes that I could not help writing a letter to myself who is sitting in front of those still lifes, maybe draped with fabrics of somewhat different national colours, maybe with the teacher droning on about half-tones, in Vilnius in the ’80s. Of course, a certain sense of drama kicked in — those still lifes had become an object of self-implied rejection and amnesia, and now it suddenly re-emerged as I was looking at her work.

“And then we gazed at the stars. Alexandra’s work with all the constellations that have been officially discarded over the course of the 20th century made me think of temporal discontinuity running through the images. We know that the light of a particular constellation may be coming from sources that are light years apart. Yet we see the constellation as a coherent image. Moreover, these images have names and these names determine what kind of narratives we read in them. And this is what happens in the text: it runs on these discontinuities; it doesn’t just contain them, nor is it merely kept together by them. However, one of the biggest twists was Alexandra’s short film. There one can see an empty classroom in which a big hand carefully places hand-sized easels one by one. It is a classroom reduced to the size of a still life. One could claim that this is how the educational system works for this type of art: it seems static and sterile, rather narrow, while in fact it just respects its own self-reproducibility, like any system. Then the only subject that one could imagine appearing on the blank sheets of paper on easels is the big hand itself: something that determines the whole situation. But perhaps there is a more elaborate twist elsewhere. The thuds of easels being placed on a wooden floor are actually someone’s footfalls. They’ve been sampled and used to create the sonic effect of wooden objects being placed on a wooden floor. Obviously, the footfall effect was produced with various film sound-making props, usually not the objects that they represent, that is, not shoes, forgive me, easels. The complex construction of such a microfiction in a film stuck with me. It hinted at illusion and control that hold together the smoothest and cleanest of surfaces. And then I thought: what if Alexandra’s catalogue in which my letter is going to be published never reaches my younger self? Will it not remain then as the sound of shoes no one has ever seen, and that were never shoes in the first place? And, like the true cyclical order of planets that keep returning to their 12 houses in astrology, I’ve returned to the letter you started to read a few minutes ago (as if the return of the 12 Neva colours to my hands hadn’t been determined by the very same laws.) Obviously the situation is different now.”

My younger self was still in front of the Greek heads. He was a bit like a plaster figure himself; like a scheme. Was he feeling stuck? I don’t know. Maybe I’ve over-indulged him in that feeling. Without expecting to verify the feelings I kept writing a letter to him, on the subject of ruins as the most alive of all the things I’d recently seen in Cairo — a city to which I am heading after the visit to Alexandra’s studio.

I don’t fully understand how these buildings unravel in space: from the bottom up or from the top down. If you look up you can see a multistorey glass and steel section first – it could be a big bank or an insurance company; then, as your eye glides up, it is suddenly cut with what looks like a residential block, with bed sheets and duvets hanging from the windows, covered in dust; and further up it continues as something not yet completed, or maybe already decayed, and actually both: clay and garbage, roofless, a sequence of differences; it could also be the facade of another building nearby, resting on a wooden cabinet on the ground. Several mirrors brush-stroked by rooms from previous life are facing cars, donkeys, men, women, fruit, treasures. A moving car suddenly splits into rusty metal and a human being that lights up a cigarette and walks into the building, or maybe out of the building – it is the same thing.

In the supermarket a different sequence is running: ‘Jingle Bells’ is looping through different voices, including children choirs, then some very sugary crooners, then more sugar, and yet more children, and yet more sugar and crooners, and palm oil in most cheese spreads.

Coming back home from two hours’ walk is like coming back from an acid trip, only the last thought remains, no images taken, as any detail is abyssmal, any pause to fix attention onto something, to capture something, is an abyss. From the avalanche of abysses one last spoil remains, a passage from Dorothea Lasky:

“I think of the eternal goal of art. A one-true-love of existence. A tree where you carve and carve words, and don’t worry about the outcome. No great halls of literature, no great monuments to house your paintings. No sculpture bed to place your well-carved marble. No, the hallows of the underworld will house our work. And so be it.

“I am she!”

Raimundas Malašauskas